Published: January 30th, 2025

by: Alison Lang, UTL News

Emily Dickinson once wrote that the brain is deeper than the sea - and nowhere is this more evident than in the latest Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library exhibit De cerebro: An exhibition of the human brain, opening January 30th and running to April 25th, 2025. Curator Alexandra Carter, the Fisher's science and medicine librarian, trawled the many corners of the Fisher's vast collections to dig up work examining the history of the human brain and the many ways humans have tried to understand it.

Her selections go far beyond medical texts into the realms of philosophy, explorations of human consciousness, psychology, pharmacology and even the paranormal. Learn more about the exhibit and Carter's curatorial process below.

UTL News: How did the idea for this exhibit come to you - and how long have you been working on it?

Alexandra Carter: So I have been working on it since before pandemic times - it's been a while! I was just on research leave, so I did most of the work in the last year.

The inspiration was actually my dad, who had a stroke a few years ago. It was a major stroke, but he suffered very minimally from the effects of that. It got me really thinking about how the brain and how very little we really understand about what's going on. I also really wanted to highlight the scope of our medical collections at U of T and the history of medicine collections. We have so much material - over 80,000 volumes. I wanted to use the brain as an entry point into these collections to explore them, and what I found was that it wasn’t just the medical sections I was drawing from – but all of the Fisher’s collections, really.

Before we delve into the details of the exhibit - you're the Fisher’s science and medicine librarian. Can you tell me a little more about your position?

Sure. I’ve been the science and medicine librarian since 2016. I only work with the Fisher collections. I don't do any selecting for the other libraries, and because we have really, really extensive medical collections and history of general science, there really needs to be at least one person working in this area. So I do acquisitions - managing purchasing and donations that come in. And anything that falls under the sciences comes to me – so a bit of teaching, exhibit curation, and cataloguing. We do a little bit of everything at the Fisher!

You definitely all wear many hats. Is this your first Fisher exhibit?

Yes, this is my first big exhibit, so it's kind of exciting that way. It was very much a learning process – although I will say that the Fisher has a pretty good system in place! But yes, it's a big project – both the exhibit and putting together the catalogue.

Is your background generally in science and medicine?

No - actually my background is art history and book history. It ends up being quite useful for the science books that are heavily illustrated. Most of the science books have many, many illustrations and plates in the back - so my background of working with printmaking and design and print and the wider historical context has been really useful.

When you started putting the exhibit together, did you have a sense of the initial trajectory? Or did the vision expand as you went along?

I knew that I wanted to look at the exhibit from multiple perspectives, not just a medical perspective – and I knew our collections would support that. But I didn’t quite know exactly which direction it would go. Ultimately, three or four themes emerged as I began working and they all correspond to collections at the Fisher – such as our big philosophy collections. These include people not just looking at what the brain is or what it looks like, but what it actually means to have a brain, and all the competing ideas that came from that, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries.

We also have a really strong psychiatry collection – Freud and Jung and all their contemporaries. So I looked at the brain from that angle as well, including Rorschach tests, and the Binet-Simon Intelligence Test, using cards. I wanted to highlight these items because they’re not actually books – they’re ephemeral items that you can use to study the history of psychology.

Finally, I looked at the brain from the social perspective as well, including the ways that people question ideas from Big Pharma – so-called “outside thinkers,” people who were doing experiments with mind-altering substances in the 50s and 60s.

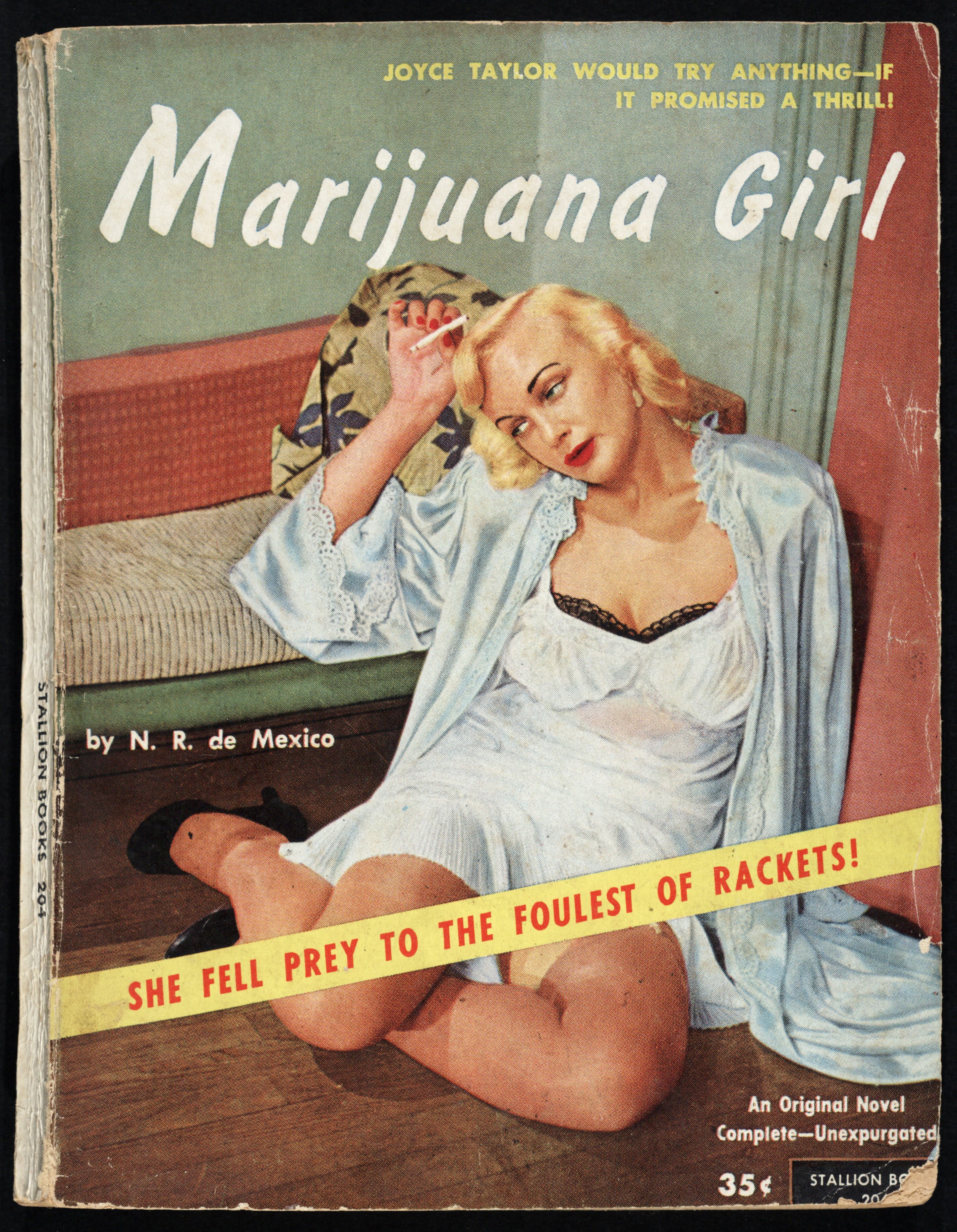

I call this section “Altered States” and it’s really just looking at drugs. We have some anti-drug propaganda too, including a fake pulp novel called Marijuana Girl, which we just acquired at the Fisher. It’s fascinating to see all these different attitudes.

I was very pleasantly surprised about how many connections I could make just using the brain as a concept. I was worried that it was just going to be a bunch of anatomical books of pictures of the brain – so it was great to be able to explore it from all these different angles. I was surprised how much I could play with the idea.

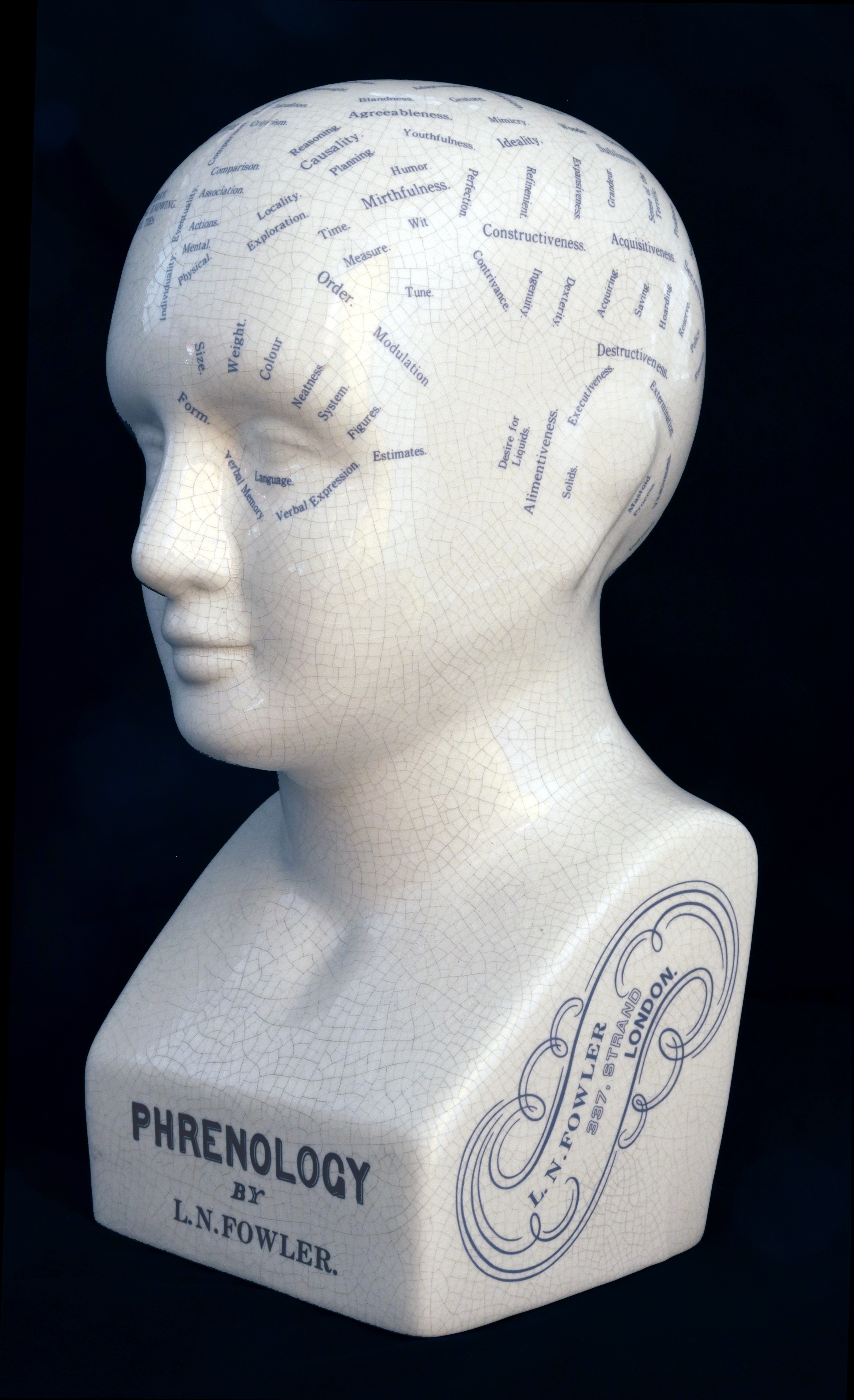

I’ve heard a little about the phrenology items that will be included in this exhibit – can you tell me a bit more about those?

In 2016, the Fisher bought a collection of phrenology busts. This is not something we would normally buy - because they’re not books. But they have a very close relationship to the books that were printed at the same time - you would buy the book in order to understand how to use the phrenological bust. If you look into the actual history, phrenology has its origins in very rigorous anatomical study. It's not just the pseudoscience that it eventually became. Franz Joseph Gall was one of their earliest people to to note cerebral localization – the idea that different parts of your brain are responsible for different things. Before this, most people just thought there was a big soup of different things going on in the brain!

Gall’s ideas got taken and out of context and became transformed into this bizarre type of fortune telling. I was surprised at that connection and how it was once an actual, legitimate science. And it got me thinking about all the other disciplines – finding connections with the brain and pharmacology, for example, and studies of psychedelics and alternative therapies. It’s interesting to think about what kinds of drugs we’ve decided are legitimate or not!

This is a huge exhibit. Did you put the entire exhibit together solo?

Yes, and I worked very closely with our conservator Maia Balint – I made the list for the exhibit and the captions. I really want to give a shout-out to Maia – she put everything up and made it look gorgeous.

Was there anything you found in your research that surprised you? I know you likely know the collections very well, so there's probably not a ton of surprises to be had….

No, there's a lot! (laughs) Let's see…. It’s actually related to phrenology.

We’ve included a more modern bust that we think is from around the 1990s. It was actually used as a promotional object for Effexor, which is an antidepressant. This item really distilled what I’m trying to say with this exhibition – sometimes, these very early ideas can get carried through into the modern setting. It’s so bizarre – if you understand what phrenology is, you wouldn't want to be using it to promote your new modern drug! I thought it was a really weird, anachronistic kind of object.

What impressions would you like people to take away from this exhibit?

I’m hoping it’s similar to the experience I had with my dad, in that whenever I think about the brain, I feel a mix of awe and wonder, and fear. It’s almost a scary feeling, how little we know about the brain.

By presenting ideas about the brain from these different angles, I hope that it gives people a sense of how hard it can be to think about the brain. I’m thinking particularly in relation to philosophy and the mind/body problem. Are we brains, or is something else going on? It’s a challenging idea to think about. The exhibition invites us to question how our ideas about the mind have been shaped by earlier ideas, and how those ideas are still around, and what they say about a so-called “normal” mental state.

People have been trying to solve this problem for a long time and we’re still not even close to fully answering these questions – and that’s quite remarkable.